Ancient Technology: Weaving in the Andes

- Madelyn Leembruggen

- Aug 28, 2023

- 7 min read

The common thread of civilization

How old are the oldest pair of blue jeans? Well, it depends on what you mean by jeans. The official patent for blue jeans was filed in 1873, but the weaving pattern that we call denim is much, much older, tracing back thousands of years. The distinctive blue of blue jeans is also older than you might think. Indigo dye that makes jeans blue has been used for at least 6,000 years. It turns out that your favorite pair of blue jeans is actually the result of centuries of technological development in weaving and dyeing which began in South America.

Table of Contents:

Ancient Blue

We know indigo has been used for at least 6,000 years because archaeologists unearthed a piece of woven cloth from an ancient village in Peru, high in the Andes mountains. The cloth was a plain weave, patterned with blue-colored stripes. Blue is a rare color in nature, and very few natural sources can make lasting blue dyes. After analyzing the cloth, researchers realized the blue was the result of indigo dye– the same plant-extract that gave the original blue jeans their color! (Read more about plant-derived dyes in our post about chemist Dr. Rangi Te Kanawa.) Carbon dating revealed the ancient Peruvian blue was approximately 1,500 years older than the blue cloth discovered in Egypt that had previously held the “oldest known blue” title.

What is Carbon Dating?

All organic materials, like plants and animals, contain carbon atoms. Carbon always has 6 protons, and it usually also has 6 neutrons in its nucleus. But there’s a radioactive isotope of carbon that has 8 neutrons in the nucleus instead of 6. The radioactive isotope is called carbon-14 (for 6 protons + 8 neutrons).

When we say that this isotope is radioactive, we mean the isotope isn’t stable, and will eventually decay into a lower-energy configuration. That decay process is pretty well understood, so we can predict how long it will take and quantify it by the half-life of the material. Carbon-14 has a half-life of 5,700 years, meaning that after 5,700 years, approximately half of the carbon-14 atoms will have decayed into energetically-stable nitrogen-14. Even though carbon-14 is rare, it sometimes gets made in Earth’s atmosphere, absorbed by plants, and eventually eaten by animals. Through this chain, all living things end up with some amount of carbon-14 in them, including you!

Scientists and archaeologists can use the amount of carbon-14 in an object to estimate its age. This method works on anything that used to be alive, including paper, leather, or cotton fibers. Based on the material, scientists can estimate how much carbon-14 it originally had, and by measuring how much carbon-14 now remains, they can calculate how much time has passed. You can learn more about isotope dating in our post about paleoclimatologist Dr. Kathleen Johnson, and radioactive decay in our post about geochemist Dr. Katsuko Saruhashi.

What else was going on 6,000 years ago in the Andes? By that point, people in the Andes had been domesticating cotton for about 2,000 years. They were spinning plant fibers into cords to make ropes, fishing nets, and baskets.

It was also probably around this time that ancient Andeans began using quipus–long cords with knotted strings attached–to perform calculations and keep records. And of course, the cloth artifact with indigo blue proves that ancient Andeans had become experts in spinning and weaving– the processes of turning fiber into thread, and thread into cloth.

On the Origin of Cloth

Every piece of cloth starts its life as a collection of loose fibers. Modern fabrics can be made with synthetic fibers, which are derived mostly from fossil fuels. But before the invention of synthetic fibers, all clothes were made from natural fibers like cotton, linen, or silk. Cotton and linen, which come from plants, are made of long strands of cellulose. But these strands are pretty short, so if we want to use them for anything, we need to spin them to combine the cellulose into a long and continuous thread.

Traditionally, spinning was an incredibly labor-intensive process done by hand, primarily by women. At that time, an experienced spinner would probably be able to generate about 200 meters (or 650 feet) of thread in one hour. While that sounds like a lot, it’s only about 4 spools of thread, which won’t get you much woven cloth. Today, most fibers are spun by industrial machines, but the basic process remains the same: tufts of loose fiber are tightly twisted together and pulled so that the fibers latch onto each other with frictional forces. If twisted and spun well, the individual fibers form a strong and sturdy thread.

Now that you’ve worked hard to turn your fiber into thread, you still have a lot of work ahead of you to turn your thread into cloth. One of the oldest methods for doing that is weaving with a loom. Looms can be quite rudimentary– you could even make your own out of sticks or cardboard!

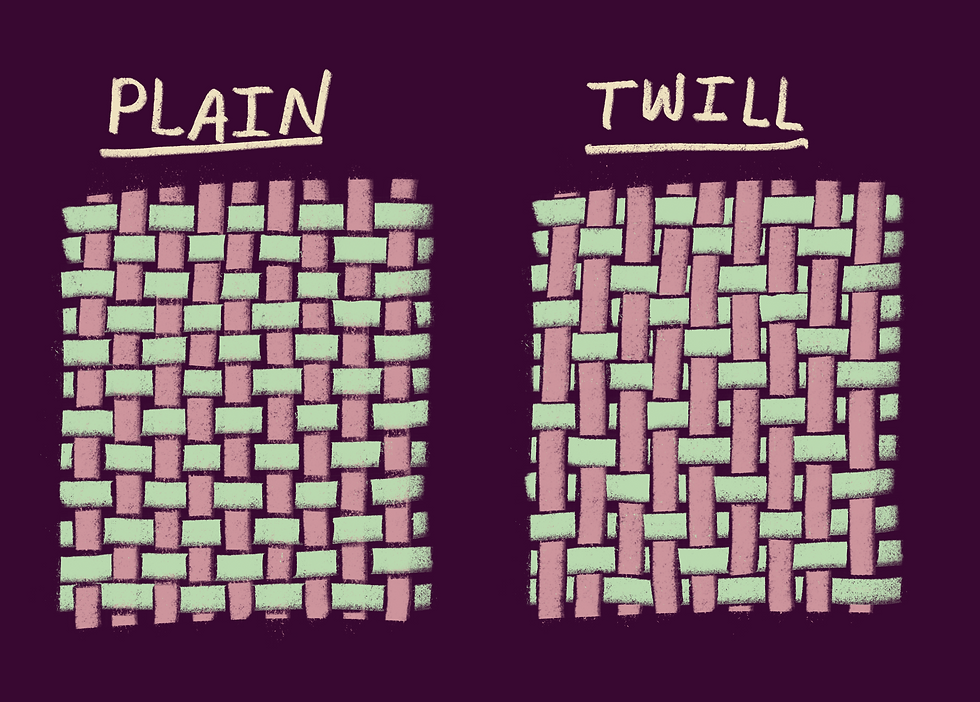

All you really need is a frame to support vertical warp threads that make up the skeleton of your cloth. You then pass your thread in and out of those vertical threads to form a horizontal pattern called the weft. The weft can be threaded in front of or behind a warp thread, and the alternating pattern is what determines the type of weave you create.

How is Woven Cloth Strong?

Thread is stronger than a collection of fluffy fibers, and cloth is even stronger than a single piece of thread. This is thanks to geometry! Weaving entangles threads together in an organized way. If a force is applied to the cloth, then the entangled threads push and pull on each other, spreading out and distributing that force. The tug that any individual thread experiences is much less than the total force applied to the cloth, so the threads are less likely to break.

A plain weave, like the artifact found in Peru, alternates over and under the warp thread. The next row would alternate under and over, and so forth. This is perhaps the most fundamental weave pattern, and it’s the easiest to learn if you’re just starting out. A slightly more intricate weave pattern is twill, where the weft goes over one warp thread, and then under two. Repeating this pattern row after row creates a slowly-shifting diagonal pattern. Denim, the material your blue jeans are made from, is a type of twill weave. The denim pattern calls for the weft to go over one warp thread, then under three.

Algorithmic Thinking

Weave and twill are pretty straightforward, but woven patterns can get incredibly complicated. Making a particular image or pattern out of woven thread requires a lot of careful thinking. The weaver has to plan the design in advance and calculate the steps needed to successfully generate the desired pattern.

They basically need to find the right algorithm to generate a pattern. An algorithm is a set of rules to be followed in a specific order to produce a desired outcome. Although we usually think of algorithms as being used by computers, woven fabrics are an excellent example of analog algorithms. If you want to weave a certain pattern, then you’ll follow the set of rules that someone previously discovered creates that pattern. Or you can create a brand new pattern by defining your own set of rules to follow!

Weavers like the ancient Andean people were really the original programmers. They invented algorithms and implemented programs to create patterns in their cloth, weaving art and practicality into their garments.

A Story's Thread

Intricate woven patterns can do more than just make clothes beautiful. They can also tell a story. For example, this woven fabric found in the Andes is estimated to be about 2,000 years old.

Historians believe that its “double fish” pattern is supposed to represent sharks, and could connect to myths of people turning into sharks, or sharks turning into people. Another example is this mantle which could be nearly 2,500 years old, and is adorned with intricate, squiggly, serpentine motifs. What kind of story do you think this fabric is telling?

Fabric patterns communicated an enormous amount of information, such as class, region of origin, gender, and profession. Textiles also kept records of religious rites and ceremonies. Intricately woven and embroidered scenes depicted deities and fantastic myths. It was common for bodies to be buried in their daily clothes, and some special garments were passed down through generations. For societies without written language, woven communication was particularly important.

Textile Technology

Can you imagine your life without textiles? A world without textiles wouldn’t have soft, fabric clothes to protect our bodies from the weather. It wouldn’t have rope to tie our bean plants to poles or knot into fishing nets. Without brilliant advancements in loom technology and the intense labor required for weaving, civilizations probably wouldn’t have been able to support diverse industry and vibrant trade. But fabrics aren’t just practical; they’re also beautiful! Patterned fabrics chronicle history, portray epic stories, and brighten our world with their color.

Thanks to textile artifacts, archaeologists have discovered so much about ancient peoples. From a small piece of blue cloth, we can tell that the ancient Andeans had sophisticated spinning and weaving industries, advanced dye technology, diverse artistic styles, and knowledge of algorithms needed to create intricate woven patterns. Weaving is a technology as old as civilization. When we pull on our blue jeans in the morning, we connect to these ancient weavers – a single, continuous thread through the fabric of time.

Written by Madelyn Leembruggen

Edited by Katie Fraser and Caroline Martin

Illustrations by Sal West

Primary sources and additional readings: Blue jeans have a 6,000-year-old Peruvian ancestor from PBS News Hour

Weaving and the Social World: 3,000 Years of Ancient Andean Textiles from Yale Art Gallery

Carbon dating identifies South America's oldest textiles from UChicago Press Journals

Beginner's Guide to Weaving: How to Use a Weaving Loom from MasterClass

Try weaving at home with these techniques!

Build (45-90 minutes): Make a Cardboard Weaving Loom and use whatever yarn you'd like to create a unique tapestry.

Experiment (20-60 minutes): Weave strips of colored paper to explore plain and twill weave patterns. You can also try to invent an algorithm for your own unique pattern!

Comments